The Lack of WLW Romance in Literature and Media

Late last year, I was accepted for a seasonal position at Indigo. My days on the job consisted of recommending and shelving novels, transactions, and returns, among other tasks such as organizing the rainbow-ordered mug display or meticulously arranging the stocking-stuffer tables. Like any retail worker, I ran into my fair share of odd customer requests — I need you to find me this book — I can’t remember the author or title, but it has a blue cover? Can you recommend a book for my mother that is a blend of mystery, romance, and historical fiction? — Fortunately, the staff’s reading interests covered a diverse range of genres, and whether someone was looking for a trending teen novel, an enticing murder mystery, or a dystopian sci-fi, someone was usually able to find something to satisfy them.

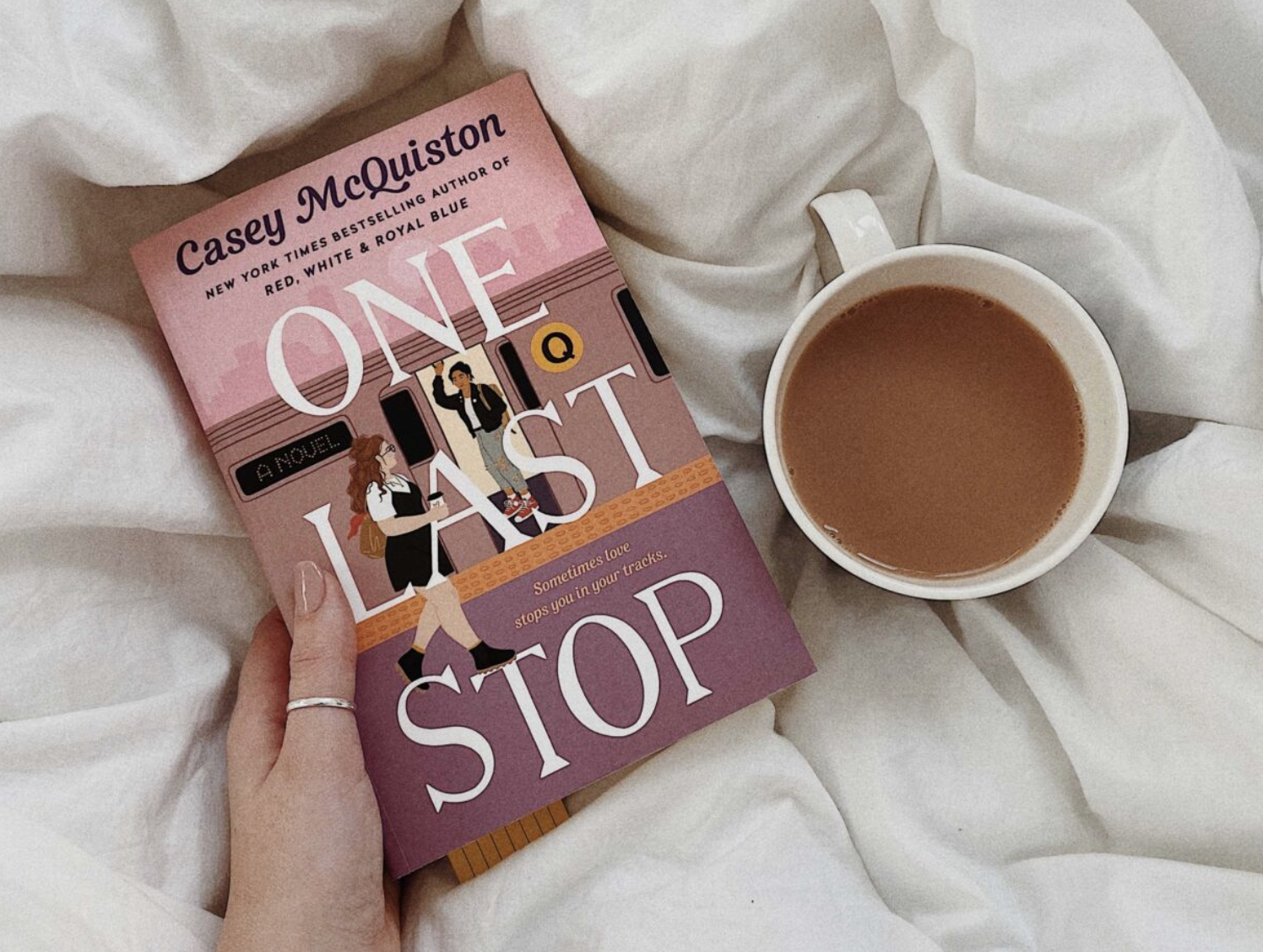

On a quiet night shift in early January, a customer came in looking for an LGTBQ book for a friend. My coworker and I collected a fair selection of teen and young adult novels for her to sift through. After just a quick glance at the stack, she clarified that she was after a WLW (women-loving women) romance. After a lengthy search of the shelves, our online database, and the internet, I was able to find just two available books: Ciara Smyth’s The Falling in Love Montage and Casey McQuiston’s One Last Stop. (Interestingly, McQuinston originally became known for the gay romance Red White and Royal Blue.). Having come up nearly empty-handed on the search for this genre, I was left confused; the sheer difference in the number of gay romances versus lesbian was a shock in and of itself. When I returned home from work, I began scouring the internet in search of answers.

After coming up empty-handed on my search for why there were so few WLW novels out there, I ditched the inquiry for almost a year. I knew it wasn’t a fluke that lesbian novels were underrepresented, but nothing was being written about this topic. I had my own opinions but assumed that any social factors or economic factors that discouraged the promotion of WLW literature should equally affect the gay literature category. When Netflix canceled its lesbian romance, First Kill, after its first season, I began to look at the topic once more. After a few days of on-and-off research, I came across an article titled “If You Say There are No Good Lesbian Books You’re Bad At Picking Books”. And although the article covered quantity not quality, the essay had some interesting insight. The author asked a similar question to mine: we are living in a time of growing representation and acceptance, and you’re telling me you can’t find any good lesbian books? The conclusion of the article was that there was lots of great writing out there, but it just doesn’t get the same attention or reach the level of popularity attained by gay books such as Heartstopper, Song of Achilles, and They Both Die at the End.

When we break down representation of men and women in all books, it becomes obvious that there are fewer female protagonists overall. As well, male readers are less likely to read books written by women. The readership of novels by the 10 best-selling male authors was fairly evenly divided by gender. In contrast, the readership of the 10 bestselling female authors skewed 81% female and just 19% male. And while straight and queer men and women will read gay romance, it seems that lesbian romance doesn’t have the same pull.

Men assume that the book is not for them… but why shouldn’t it be? While working at the bookstore, I sold multiple copies of Heartstopper, a gay teen romance, to customers who were diverse in both gender and sexuality. It does beg the question, if the bookstore had a lesbian graphic novel, would the readership be as varied? As a consequence of this narrow support system, sapphic books don’t get the attention or promotion they deserve. It creates a circle. Publishers and bookstores are hesitant to commission and promote this genre, which leads to a smaller potential audience for a book. This, in turn, means lower profits for the publisher and, in the longer term, fewer lesbian books in bookstores.

With the success of lesbian novels such as The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo and One Last Stop, there’s hope for support to grow the audience for sapphic books in the future. After First Kill’s success — it peaked at No. 3, with 50 million hours viewed in its first week — dominant streaming companies should be reconsidering what viewers want. Will sticking to the secure confines of straight, white characters and relationships continue to be considered the only recipe for success as times change and audiences become more diverse? I believe growing representation in YA books is leading the next generation of readers and authors into a world of opportunity — and this is only the beginning.