Antonioni’s Trilogy on Modernity and Its Discontent

This year’s Met Gala theme “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion” featured approximately 100 garments that embody the nation’s fashion from throughout the 20th and 21st century. The pieces are organized into 12 factions: Nostalgia, Belonging, Delight, Joy, Wonder, Affinity, Confidence, Strength, Desire, Assurance, Comfort, and Consciousness.

One ensemble by Matthew Adams Dolan entitled Dreaminess––the quality or state of being dreamy (given to dreaming or fantasy)––draws inspiration from John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s 1969 Vietnam protest “Bed-Ins for Peace.” The “ill-fitting pajamas” allude to the discontent surrounding the supposed ease and comfort of American life and represent the American dream. Particularly important to Dolan is the need for solace and hope during times of chaos.

The notion that clothes are absurd and beyond logical explanation is a longstanding belief. Tied to the design problem that exists in our everyday fashion, this harkens back to the true, primordial design problem––human anatomy. The architectural approach to clothing begs to differ, stating that for each question or problem that the human body proposes, clothing attempts to assuage, and therefore results from logical processes.

Austrian-American writer Bernard Rudofsky’s seminal essay “Are Clothes Modern?” disturbs people’s relationship with clothing and the supposed illogic that circumscribes it. Are the clothes we wear today anachronistic? Harmful? From this architectural approach to clothing, he argues that clothes are functional, designed with purpose and are actively pursuing that purpose, whether it be power, sexuality, etc.

Italian art cinema forerunner Michelangelo Antonioni, particularly famed for his “trilogy on modernity and its discontents,” captures elusive mood pieces focusing on the very lack of purpose and pursuit that haunts his characters. His work exhibits sensual stories of mishaps and adventures within a dreamy atmosphere. His characters navigate seduction and enterprise while struggling with their own dizzying ennui. Usually, the bigger picture of each of his films has to do with languid existentialism and the tragedy of modern beauty. His work is definitely for the real film fanatics out there––Criterion Channel subscribers and lovers of Cleo From 5 to 7 (1962). With masterful abstraction, he favors the introspective and the ambiguous.

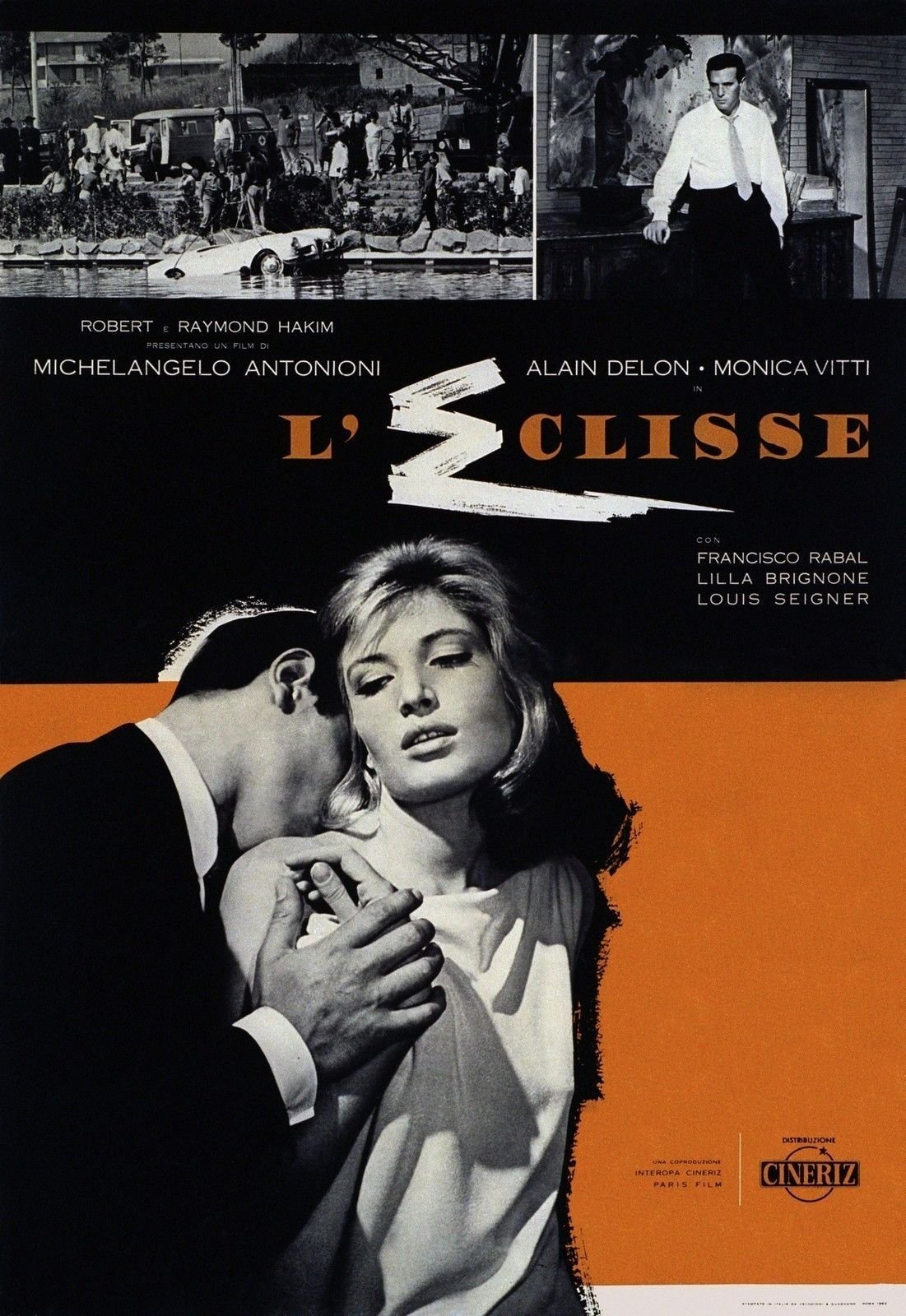

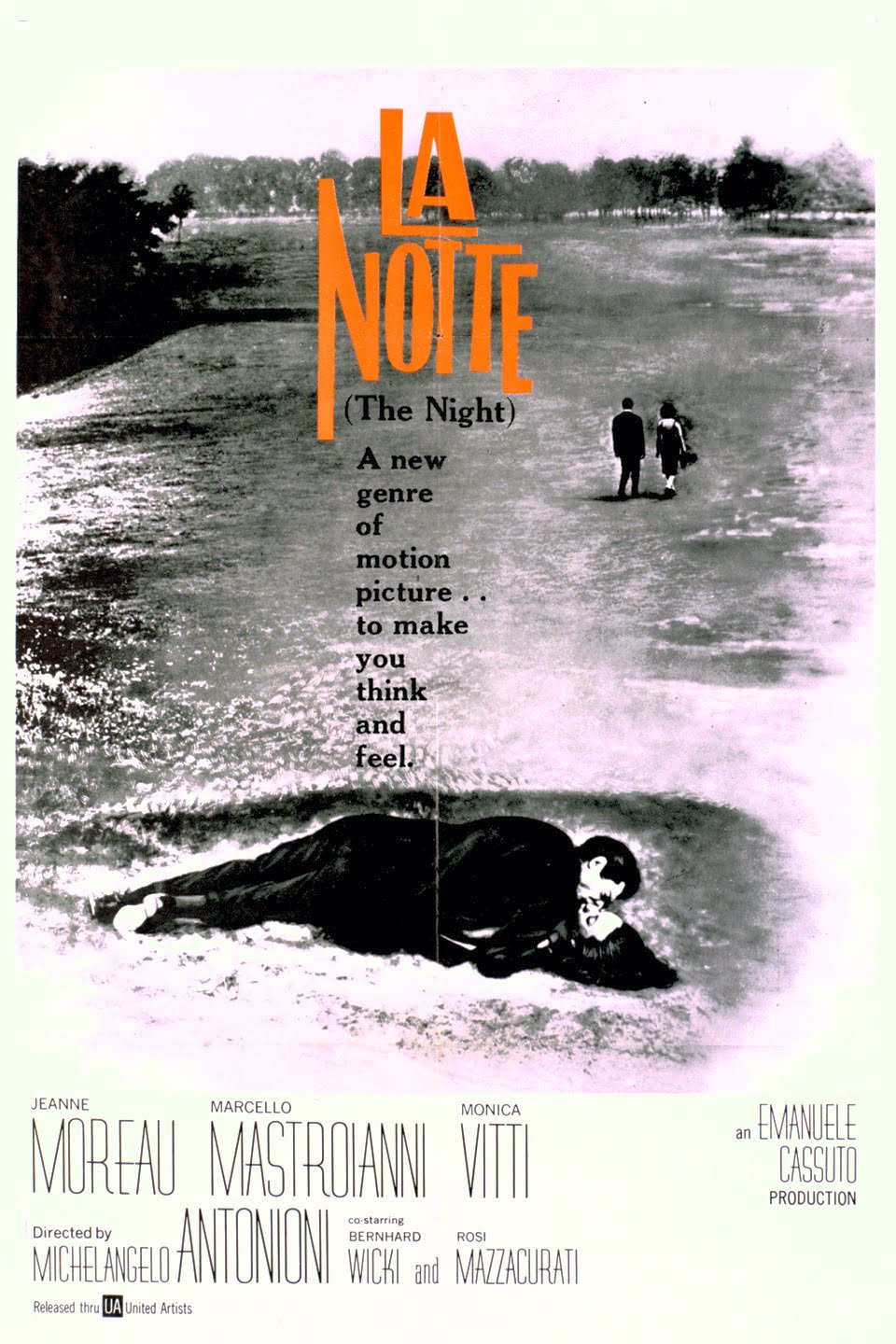

The three films that comprise the “trilogy on modernity and its discontents” are L’Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961), and L’Eclisse (1962). Each with their own smoky surrealist atmosphere, characters stumble through their gluttony and desires in places of supreme dissatisfaction––lush vacations, decadent parties, or seductive cityscapes. The premise of contemporary malaise is simple: centuries worth of war, tyranny, and tyrade result in a picturesque world still racked with the uncertainty and desperation of its human subjects. Without purpose, characters move through their daily lives with discontent, harboring their unwieldy expectations of success and triumph.

Antonioni focuses on bourgeois society and therefore his films concern themselves solely with the problems that befall modern “educated, white-collar thinkers”. Thus, this “discontent” is fairly short-sighted, though his critiques on modernity do not connote feelings of nostalgia for the premodern. A post-religious modernist himself, Antonioni has dissected morality in the modern setting and rejected it in all forms. The trilogy agrees with Marxist ideology that mechanization and technology has broken down our moral boundaries, even in terms of sexuality. The eroticism throughout the trilogy as well as the rest of his filmography casts a spell on antiquated repression in favor of listless libidinal impulses. His work looks toward a new moral attitude, possibly one that renounces morality completely for all its constriction and shame.

Contemporary mores are particularly preoccupied with sexio-politics. Since premodernity and beyond, psychosexual impulses have been hedged by guilt and distrust. Antonioni notes that modernity favors consumerist eroticism, where psychological despair footnotes any romantic desire. Truly, the feeling best captured in his trilogy is intense yearning. And, in a post-industrial hyper-capitalist milieu, people and one’s relationships are disposable and replaceable. This concept creates the alienation seen in the trilogy.

Dehumanized and desperate, the women engage in loveless affairs only to end up as dissatisfied as they were before. Modern couples, estranged from passion and pursuit, must subject themselves to a consumerist social atmosphere wrought with anxiety. Not condemning these players of modernity, Antonioni instead discusses the fragility and moral ambivalence of the culture from which they are born. Antonioni’s trilogy communicates the tragedy of modernity––communal alienation and the futility of people’s passions.